Conservation Practices Virtual Education Series: A Conversation with Keynote Speaker Kyle Hutchison

Kyle: I’m Kyle Hutchison. I am a partner in a multiple generation family farm here on the shore headquartered in Cordova, Talbot County. My cousin and I are the fifth generation; there’s the two of us. And then his father, my father, and an uncle still involved. At one time, there was five brothers at the farm together. And we’re truly a family-farm operation. There’s the five of us and we have one full-time hired guy and a couple part-time help. But other than that, we do it all.

So we farm here on the Mid-Shore in Talbot and Caroline Counties. Corn, wheat feed, barley – seed barley, malting barley – cucumbers, pickling cucumbers, baby lima beans, green peas. That’s probably about it, it’s about seven or eight different crops. We try to be stewards – I guess that we feel like that you know, farm profitability and good environmental practices don’t have to be mutually exclusive so they can be combined. We believe that. We’ve been involved over the years in a lot of different practices conservation wise, and we’ll continue to do so.

Larisa: So that leads almost perfectly into our second question, which is what kind of conservation practices do you implement or have in place on your farms? Whether they be easements, soil health management, habitat restoration – would just love to know more about what you do.

Kyle: Right. Yes. We certainly believe in preserving farmland. So, we have land that is in Rural Legacy easements, and also MALPF, Maryland Agricultural Land [Preservation] Foundation easements. To preserve farming on the shore, you have to preserve the resource, which is the land. So we’re believers in that. The last farm that was purchased in 2010, we probably couldn’t have done it without putting an easement on it at the same time we purchased it, because that made the balance affordable after we received money for the easement.

We do all kinds of conservation practices. We’re certainly big in to cover crops and have been since the beginning. Back in 2021, we planted 85% of our eligible acres to cover crops. The only reason we didn’t plant the other 15% was because we ran out of time with the seeding deadline. I mean, we would plant 100% if we could. We practice several different types of nitrogen management, and apply many times over the growing season to meet the crop needs. We practice No-Till, we have three nitrogen bioreactors on farms that we own, and might possibly do some more. We started the first one of those eight years ago, and it was more of experimental practice back then. They were trying to figure out how they worked. And I think they’ve got this to the point now where it’s a proven practice. And then we also lately [have] gotten into some drainage water management. That’s a big thing with the WIP (Watershed Implementation Plan) goals and ShoreRivers is working on that. We did a partner site with them in Caroline County three years ago, and that’s been working well. I’m sure there’s a couple other things I forgot. That’s a basic overview.

“To preserve farming on the shore, you have to preserve the resource, which is the land” - Kyle Hutchison

Larisa: I had seen in one of your photos that you had sent by that it seems like you had like a wetland of sorts over one of the bioreactors.

Kyle: The wetland was where we did the drainage water management project. The purpose of the wetland there was in the picture, you can see the white pipes sticking out of the bank on the right-hand side. And the tile lines from the field drain into that wetland. That was a created wetland, it was not there before. The water stays in there while some of the nutrients and sediment settle out, before it outlets into the stream. So, it is a nutrient management [and] sediment management practice there. And that was done in conjunction with ShoreRivers – Tim Rosen at ShoreRivers.

Image: Wetland associated with drainage management on the Hutchison farm.

Larisa: So, if I can ask, along with ShoreRivers, who else have you worked with to implement these practices? What other organizations?

Kyle: Certainly, the local Soil Conservation District is big in helping. I actually serve on the board. I’m the Treasurer in Talbot County, and I serve on the board of the Talbot County Soil Conservation District. They certainly got many practices. Too many to name, really. If you’re interested in something, you can probably find some funding to do it. NRCS (Natural Resources Conservation Service) also, which is another government organization. We have also worked with Ridge to Reefs on one of the bioreactor projects – Andrew Koslow was involved in that. That’s all I can think of right at the moment.

Larisa: Now, it’s interesting, we haven’t had anyone mention Ridge to Reefs before. So that’s a little different than what we’ve typically heard. I did hear you briefly mention funding for these kinds of projects. Do you find that most of these implementations do have some kind cost-share funding? Or like an incentive payment behind them, or are they more so returns on investments?

Kyle: To this point, there’s been a funding source behind them. For example, the Bioreactors were funded with grants. We said we would provide the land and maintenance. And as I mentioned, it was an experimental practice at that time. I don’t even know how many there [are] in the whole state of Maryland, maybe ten or 12. There isn’t that many, period, even at this time. But that was an experimental practice there.

There’s grant funding for the drainage project. They were looking at subsurface drainage versus surface drainage, and quantifying the sediments and nutrients in both to determine what is the best way to drain and make productive farmland. That particular farm had been tile drained in the 1950s, and it was failing. So, this was just basically retrofitting a system that was already there.

The funding does help things get a return on investment for sure. Sometimes, things won’t work without some funding. I mean, you would not be able to afford to do it [otherwise]. Some of that may be changing with some of the Bay Restoration funds, as they’re moving away from treating sewage and working on sewage treatment plants, to more of an agricultural focus. There may be different ways to get return on investment using funds like that. But that’s kind of in the future, that’s not really happening right now.

Image: Bioreactor on Hutchison farm.

Larisa: I’m also curious to know which one of your conservation practices perhaps took the longest to implement, whether it be from initial inquiry to the relevant office to actually being, you know, in the ground and functional. Did you find that there might have been some hindrances to your farming operation in order to permit the time it would take to implement some of this?

Kyle: From a time perspective or from a learning curve perspective? There’s a difference in my mind, I guess.

Larisa: I guess we’re looking at a time perspective, because I know a lot of the applications for cost shares in different programs are on an annual cycle with a deadline and a waiting list.

Kyle: Right. And there’s engineering components that have to be completed, and there are standards that have to be met. And sometimes that gets a little frustrating, because you get on a list, then it takes time to work through that. But I guess I really haven’t been disappointed in anything. I expect that it is a process and that it takes time. So that’s kind of how I feel about it. It doesn’t upset me if, you know – if it drags on for years, yes. But six months, a year… just seems to be typical. Now, some of the practices that we’ve chosen to do on the farm have a learning curve. So that’s a little different. But yeah.

Larisa: Sure. I’m curious to know more about that, but I think I maybe want to ask first – so after you implement the practice, you know, the time has elapsed, it’s in the ground, it’s working. For example, Eastern Shore Land Conservancy sends a stewardship monitor out once a year to check the condition of the easement. Do you have any other kinds of monitors or check-ins for any of your other practices from an organization?

Kyle: The bioreactors have to be maintained and they’re checked on. But really, not a whole lot. I guess as farmers we do more than anything, because I’m there every day, and I see it. So, I’m the one that really monitors it, or somebody [else] on the farm, somebody that’s knowledgeable. I do all the application on our farm, so I’m across every acre on the farm probably five times every year. So, I see things throughout the growing season, pay attention to things. It really comes back to the manager or the owner really.

Image: Overlook of a field on Hutchison’s farm in Talbot County.

Larisa: So would you mind then elaborating a little bit on what you mean by sometimes there’s a learning curve behind implementing some of these practices?

Kyle: Sure. For example, nitrogen management is a big deal, and we typically will use three approaches to managing our nitrogen in corn. We’ll make split application – so in a corn crop, we’ll apply nitrogen five times throughout the growing season to try to match application to crop needs. But when it comes to the side dress application, which is in the last application, we typically go later in the growing season when the corn is four to five foot tall, and we pull nitrate tests from the soil to determine how much residual nitrogen is there. We also lately have been doing the Cornell Adapt-N program, which is a nitrogen modeling program.

The third thing that we’re doing is running active sensors. So the application rate that I run has sensors on it, and it reads biomass and chlorophyll. As you go across the field, it will change the rate that you’re applying based on an algorithm and certain parameters that you have in there. What it basically does is it applies the nitrogen where it is most needed in the field. Normally you would go out there and say, if this field needs 50 pounds of nitrogen, you would put 50 pounds across every acre on the whole field. This sensor can say, “You just went through that area or you’re going through that area. And the corn, it was too wet and it drowned out, and it’s yellow, and it is two inches tall and it’s never going to make grain. So we’re not going to apply anything there. It’s going to be a zero”. So it just moves the nitrogen around in the field, and I feel that’s a better use of resources. That’s something that took three or four years to grasp that concept. That’s probably a challenge.

The problem with using three approaches is sometimes you get three different answers. They all have some science behind them, but which one is right? You’ve got to make a subjective decision on which one you think is right, because you’ve got all the input correctly in, but it gives you three different answers. And sometimes the answers are vastly different, right? In nature, it’s just hard to manage. It’s tricky. So we just try to do the best we can.

Larisa: So what are some of the benefits do you think you’ve been seeing from implementing these conservation practices? I mean, those benefits can be economic, environmental – whatever you feel like you’ve really gained from choosing to apply them.

Kyle: Definitely. For cover crops, they do prevent erosion. We’re big believers in doing that for that reason. And they also provide weed suppression, which is used for the herbicide for the following year. You can use less, or different – you can’t get away with zero, but you can use less. So that’s definitely a benefit.

I do believe we’re seeing soil health benefits also from the practices. We do a lot of No-Till. And then we are looking into how we’re going to do some Strip Till this year, where you just only till a six-inch band that you’re going to plant in, and you leave the rest of the soil undisturbed. So there are some soil health benefits there, if you can figure out how to afford the machine to do that, or if you can justify the cost, let’s put it that way. So there’s certainly environmental benefits, too less sediment, less nutrients leaving your land, which you paid to put them on there, I would like to see it in there. I don’t want it in the waterways either.

“Farm profitability and good environmental practices don't have to be mutually exclusive” - Kyle Hutchison

Larisa: So how about any potential negatives or drawbacks, anything that hasn’t gone quite to plan?

Kyle: Yes, of course. That’s life, isn’t it? The practices, for the most part – the bioreactor, drainage, things like that, they pretty much take care of themselves and they don’t directly impact farm land per se. I mean, they may sit on farmland, but other than that area that where they need to be, they’re really not directly impacting what you’re doing on the land. We’ve had a mixed experience with cover crops in that sometimes they invite some pests that I would normally not have to deal with and I have to spray an extra time with an insecticide, or replant, or do some other things because the cover crop was a host to a pest that destroyed part of the crop. So you can’t really ever quite figure that out. It depends on the year, and you can manage as best you can, but it’s a challenge sometimes. And sometimes you’re not always going to be right, no matter what you do. You could do the one thing this year, and it’ll be the exact right answer, and you do the same thing the following year and it could be the exact wrong answer. But that’s when you’re dealing with Mother Nature — that’s the way it is. Just do the best you can.

Larisa: Sounds like good advice to give to somebody who’s maybe considering implementing some new practices. Knowing what you know now, having experience, is there anything else that you would caution a landowner or farmer who’s interested and maybe adopting some of these practices?

Kyle: I think you have to understand the contract, and what’s expected of you. That’s very important. Sometimes those things get glossed over. But as far as the partners we have, I don’t have any reservation with dealing with any of them. I like dealing with every one of them. So like I say, we’ll continue to do so and do more in the future.

Larisa: Then I guess one last question for you, which kind of draws on something that you had said earlier about like your beliefs – like you believe in applying a No-Till practice. What’s prompted you to start implementing these practices in the first place? What really drew them to you? Or what is it that you generally believe in?

Kyle: The farming and our agriculture, it’s all on a continuum. I mean, you’re always trying to do better — I’m always trying to do so. We might be doing pretty good, but you can always be doing better. So I like to strive, and we like the challenge of doing things, improving all the time. You don’t get to the finish line and you’re done. It’s like I say, it’s a continuum. You’re always trying to do better, and be less impactful about what you have to do. I mean, for us, it’s our business. We have to make a living. It’s to put food on the table. It’s how I pay for my son’s college. It’s got to be profitable. At the same time, you can implement some of these practices, and there’s exciting things coming down the road. Biologicals are a big deal. We’re actually trying three different ones this coming year. Two of them help the plant fix nitrogen out of the air and utilize it, so you can reduce the nutrients that you have to apply. And the third one makes the certain nutrients in the soil nitrogen and phosphorus more available to the plant. So there’s that in the emerging science. I think that’s really going to change things in the next five years and maybe reduce our reliance on having to apply nutrients. Maybe we can do it less, and get the same result. Or better.

Larisa: Great. Well, I think I’ve pretty much hit all of the major questions I wanted to ask you, so I guess I’ll open to you now if there’s anything that you’d like to elaborate on. Or if there’s anything you really want to get out there to the audience.

Kyle: Not really. I think we touched on most of my notes there. Would you like me to explain some of the pictures?

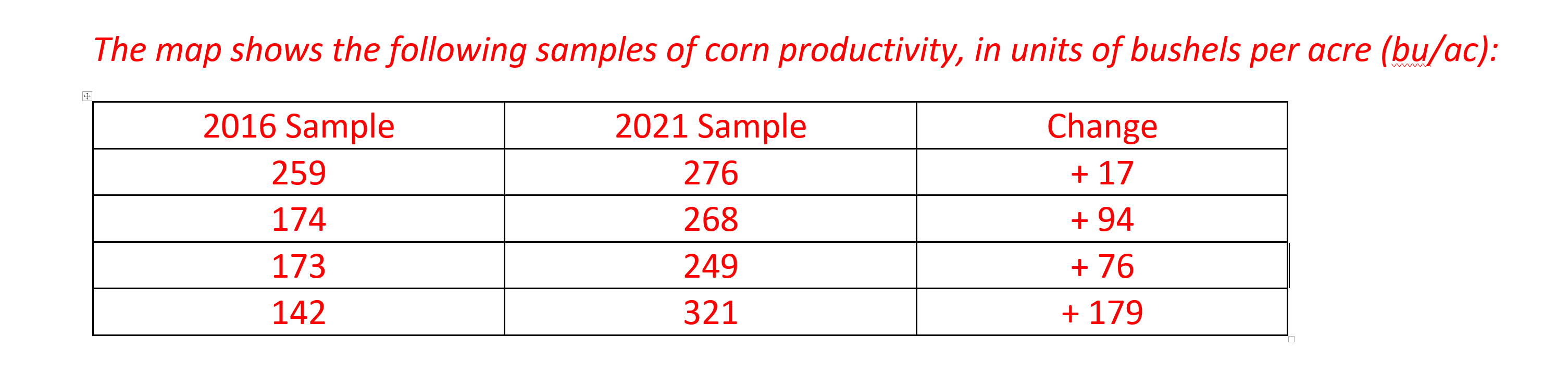

Kyle: In the earlier map, the earlier year, the red and yellow are the areas that were severely impacted because they were too wet. The soil was saturated and the corn plant basically drowned in those yellow areas and did not produce grain. So that was before we did the drainage tile project. And the other map is after we did it. And you can see it’s mostly green, and then I circled the areas and have the yield — I queried an area within the area that I circled and I have the yield inside. The number 142, or whatever the numbers are, that’s the yield within that block of that queried area. So you’ll see on the second map, that dark green, the yields are higher and it shows an impact of what the drainage will do from an agronomic standpoint.

Larisa: That is quite a difference, just like flipping back and forth between the two photos.

Kyle: And that’s how you decide whether it’s economically viable to do that kind of stuff or not. We have everything that we’re doing basically cloud based now. So I’ve got at least ten years of data that I can look back on and make decisions, based on yield data and application data and other things. So that helps figure out which practices would be best for the farm.

Larisa: I’m always continually impressed by how much technology plays a role in conservation practices, especially tile drainage. Having that little solar panel box out in a field that collects data on where your water table is and being able to program it? That just all really, for lack of better words, blows my mind.

Kyle: Somebody smarter than us to figure that out, right?

Larisa: Yeah, exactly. Yes. Was there anything else that you wanted to mention about the bioreactors?

Kyle: Not really. The initial designs that we have were experimental also. I think they’ve got it figured out now, two of them really aren’t functioning greatly now because of some design issues, I think. But the third one we have is better. So I think that’s why we were willing to work with ShoreRivers, and Ridge to Reefs, to figure this out. You know, somebody’s got to be the guinea pig and start. So we said “we’re willing to work with you”. So that’s the bioreactors. The data that we have, we tested it with Drew Koslow’s help, or he tested it, and I tested it some too, over a two year period. I believe it showed that it reduced the nitrate in the ditch water at — reduced it by 85%. So it took 85% of the nitrate out of the water once it went through it.

***

We ended our interview with Mr. Hutchison here, thanking him for his time and for sharing his invaluable advice and story. ESLC is greatly appreciative for the opportunity to learn more about his family’s legacy and their sustainable farming practice here on the Shore.

Image: Hutchison farm in Talbot County.