A Conservation Conversation at Stoney Ridge

“Everything I’m doing has a history kick to it,” says former ESLC board member C. A. Porter Hopkins. In addition to passionately sharing his knowledge of local history, Hopkins has played an important part in history himself, serving as a state senator, working as a Korean War veteran, helping to found the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, chairing the committee that preserved Assateague, assisting in preservation of the Chesapeake Bay Environmental Center (an ESLC easement since 1998) and, of course, protecting his Stoney Ridge farm with an Eastern Shore Land Conservancy easement. First protected in 1978, Stoney Ridge’s 179 acres include grain fields, forests, wetlands, and waterfront, now dedicated as open space forever.

This summer we had the opportunity to catch up with Hopkins in Dorchester County during an annual monitoring visit. Fields of beans, sunflowers, corn, and milo were surrounded by thick buffers of woodland and July stands of wild fennel, wineberries, milkweed, and Hopkins’ favorite “rabbit tobacco,” already starting to open its soft yellow stalk of blooms. We learned about the Hopkins’ work hosting wounded warriors for hunting retreats on the property. And we explored unruly stands of English ivy, gravelly waterfronts that served as a portage for Native Americans, and “Patti’s Pond” where a clutch of new wood ducks had just left the nest. Both artists, Porter and Patti Hopkins have lived on the farm for over forty years and still find themselves captivated by tree frogs hiding in fig trees, nodding sunflowers, and scavenging buzzards. Tag along for our conservation conversation with Porter Hopkins.

A frog hides under ripening figs at Stoney Ridge.

Where are you from and how did you become involved in conservation?

I grew up in Baltimore County and I’m going to tell you why I’m on the Eastern Shore—there were too many people up there in Baltimore County. At that point I’d lived there most of my life. I’d been away to school and I’d been in the service for a while. I was working. I was teaching school. I got elected to the legislature up there. I spent twelve years in the Maryland General Assembly, the last four as a state senator with my district running from Westminster across the top of Baltimore County all the way to Havre de Grace. It was a great district to be representing. I had farms there and was farming. That’s how I got involved in conservation; it was through a couple of wonderful old men, one named Talbot Denmead who wrote the original waterfowl law, setting up seasons and bag limits. And another guy named Malcolm King who worked for the Game and Inland Fish Commission. After he got out of the service in the late 40’s he wanted to see ponds. He wanted our waters cleaned up. He wanted to save our streams. Somebody talked me into joining the Isaac Walton league. These guys were great. Fun people to be around. I agreed with everything they were trying to do. So that’s how I got into it.

What did you do next and when did you move to the Eastern Shore?

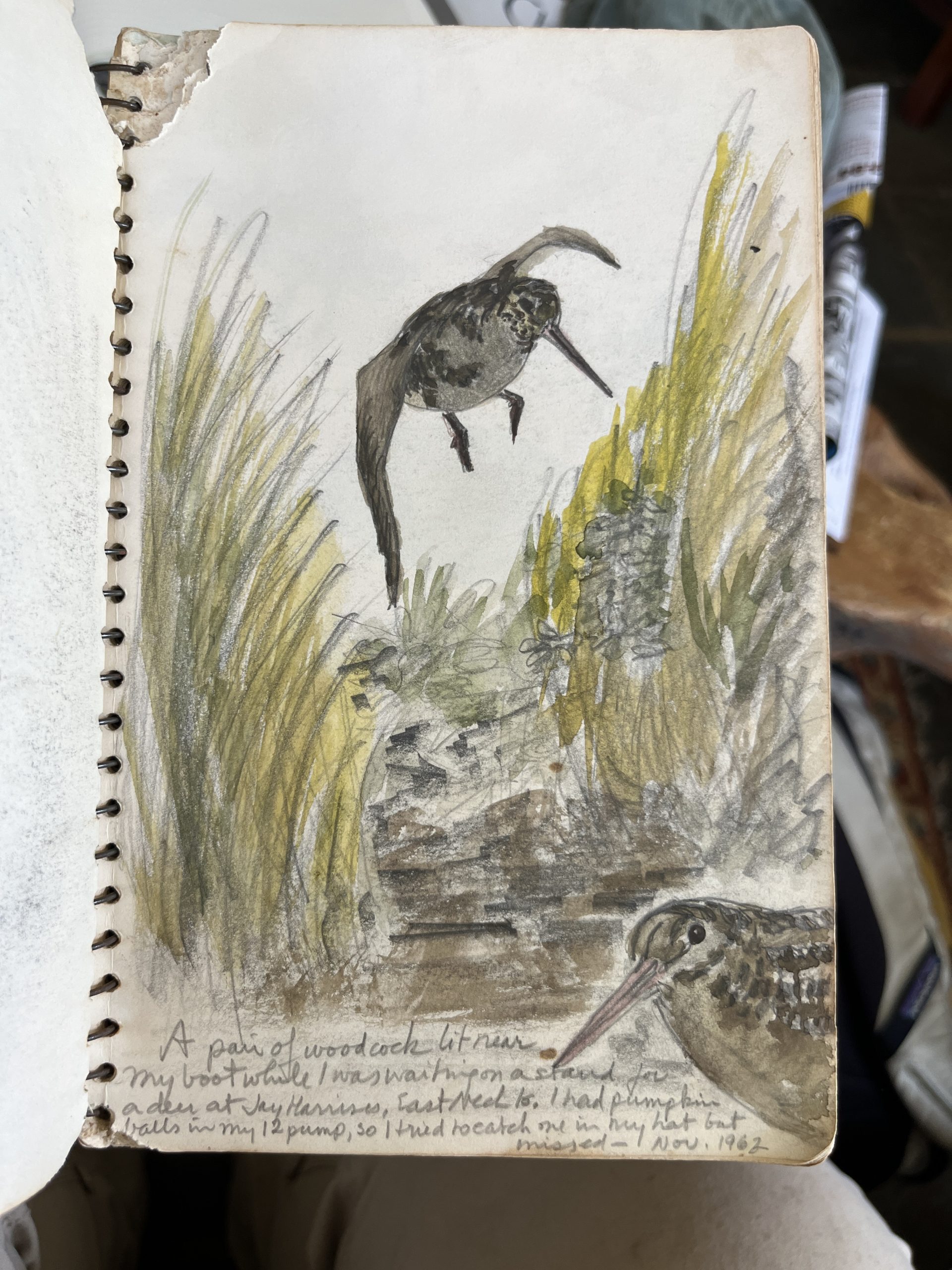

I ended up as the editor of the Maryland Conservationist and also the editor of the Maryland Historical Magazine. Everything I’m doing has a history kick to it. Including my family. The Hopkins were all from over here on the Eastern Shore. Did you ever hear of Hopkins Neck? My grandfather was the last Hopkins born on Hopkins Neck back in the 1840s. I bought this farm in ‘76. My term in the legislature ended in ‘78. I packed all my stuff in a couple of trucks and moved down here full time in ’78, but I spent almost all my time running back and forth over here because I had a couple pieces of property in Dorchester County. I’m a duck hunter. I love waterfowl. Love looking at them, drawing them, carving them. I got involved with ESLC and I knew Russ Brinsfield.

What is your earliest memory of the Eastern Shore?

I had so many cousins living next door who were from Easton. One of the Hopkins, my great grandfather, was foreman of the jury in Easton when the Yankee troops came in and took Judge Carmichael off the bench—the only time a federal judge has been removed by force in the history of the country. I can’t remember the first time I saw the Eastern Shore. I remember very clearly being on the ferry with my father, before World War II, to go from the downtown harbor of Baltimore to Rock Hall. And getting a ride from Rock Hall down to Eastern Neck Island to the hunting club. I don’t think I shot because I think I was probably too young to be shooting then. But by the time I was eight or nine years old I’d learned to handle a gun pretty well. That probably was my first memory. The Eastern Shore was then and still is the main part of my life. It’s what I call home. It’s maybe not where I grew up, but I’ve spent forty years here and haven’t been back on the western shore.

A soybean field at Stoney Ridge.

Tell us more about your conservation easement.

I’ve never been unhappy about anything I’ve done with these easements. If you want to preserve anything, preserve land. And the only way you can do it is by putting a legal restriction on what can happen to it. The day I signed to buy this place the property was owned by five or six men who wanted to develop it. I can remember saying, “The main reason I’m buying this property is because I don’t want to see it developed.” I was on the Chesapeake Bay Foundation Board. We had talked about an easement program. Arthur Sherwood, who was the founder of it (CBF) and was a good friend of mine, was sitting in a goose blind with me one beautiful day, watching geese come. I thought, “We’re going to get a shot here, Arthur.” Next thing I knew he stood up and fired the gun off. I said, “What’d you do you that for? You spooked them all.” He fired and off they went. And he said, “I just thought it was the thing to do.” I said, “Well, I think probably the thing for me to do is put an easement on it so we can’t have people like you down here bugging them all the time.” Arthur had a sense of humor. So, I had this place that was the first easement for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. They were the ones to be supervising it. Something happened and somebody said, “We’ve got to get it involved with either a land trust or with the state environmental trust,” and Eastern Shore Land Conservancy got involved.

How did you first learn about ESLC?

I learned about it probably through Russ Brinsfield. We had a pretty active farm club here until COVID. It was a tidewater farm club, mostly Talbot and Dorchester and some of the state employees and county employees. We had thirty or forty people for lunch and speakers. Russell Brinsfield was a member and Rob [Etgen] must have come. The group got together and said we ought to have some kind of a land trust. And there were already people who had given their lands or put the easements on. And there were several of them down the Neck here. I don’t think any of them I’m thinking of now are alive. But I’m sure there’s still an easement on the place.

Why did you choose to protect your land with an easement?

I didn’t want to see it developed. There’s too much development going on. There’s one farm that a bunch of us shot for years right behind the graveyard coming into town and the last couple years there have been 25 houses built back in there. And I wasn’t just trying to preserve the hunting on the place. I’m fascinated by the American natives. This farm was heavily used by them over the years. Almost every time there’s a major storm we’ll find an artifact out here on the beach or out in the field. We don’t use the plow much anymore but if you plowed there would be two to three major collections. I have two neighbors who, every time we’d have a low tide, they’d be here in a boat, going to shore, looking up and down the beach for arrowheads or whatever they could find. It still draws people. And it’s Stoney Ridge. We’re in a belt here that goes all the way across to Oxford. There isn’t any stone anywhere else. But there’s a lot of stone from here on across. This place here, the first six to eight years I spent most of my time digging stone and piling it up on the beach. It’s a rather interesting geological formation. We’ve got natural oyster beds out here that are still producing. They’ve closed most of them for one reason or another but my next-door neighbor has got some leased beds. And another guy across the creek from me was growing them in floats. The Eastern Shore is the Eastern Shore. If you’ve never been anywhere else maybe you wouldn’t think so much of it. But it doesn’t take many trips away from here to realize that we’re the best place of all.

What positive changes do you hope to see on the Eastern Shore?

I hope that they we can preserve even more than 30% of the Eastern Shore. The only way they’re going to do that is get people back into towns that have since scattered and aren’t where they used to be. I don’t think we can afford to give up our farmlands the way that it’s happening across the rest of the country. Isn’t that the main reason for ESLC? To save lands? And to save lands that are productive and diverse and have the timber and the marsh and the ponds? It’s not all going to be saved. We’re not going to be able to do that. But we sure can do better than generations before us were doing.

Tell us about a favorite wild plant of yours on your easement.

My favorite wild plant would have to be “rabbit tobacco.” It’s a mullein with great big wide leaves. It gets to be about four and a half feet tall with a yellow blossom on it. It’s a wild mullein. I bet you nobody’s said that’s one of their favorite plants. When I first bought the place the CREP program would pay you to plant or to leave strips, grass strips mostly. The forty years that I’ve been doing it… I have some of the greatest looking wildlife strips around this farm. They’re all ones that I just let go. None of them can I say were my favorites. One point you might make about the Eastern Shore is that we have lost some of our major trees. We lost the Wye Oak. That was a major tree. I had a tree like that out front that had three trunks growing out of it and it blew down in a storm. These were massive trunks. They weren’t as big as the Wye Oak but we had a neighbor who had a tree almost as big as the Wye Oak right out in the middle of a corn field. And that disappeared in a storm maybe about 35 years ago. I’m distressed to be able to tell you that three of the major trees in my life are gone. One of them was the American chestnut. The farm that I had in Baltimore County had a bunch of American chestnuts still coming up out of stumps. They’d get to be twenty-feet-tall or so. Every now and then we’d have a blossom or two. Then whatever killed the American chestnut got them too. I just planted an American chestnut. I want to see the American chestnut come back as one of the major trees on the Eastern Shore and the eastern half of the country. The Dutch elm disease hit the American elm which was the beautiful tree in every small town in America until World War II. We don’t have any more American elms. They’re practically all gone. And the third tree is one that you’re seeing all around you now, the American ash. Green ash borer has done a number on all the ash trees. You’ll see great big dead trees on every farm over here. So three of the major trees of my lifetime have disappeared from whatever cause, mostly bugs or worms or moths.

Tell us more about the wildlife on your easement.

This area is very close to seeing the wild turkey come back. I never would’ve thought I’d see the wild turkey come back. But when the turkey came back we lost all our bobwhite quail. I had seven coveys on the farm when I bought it and I don’t have one and haven’t heard a wild bird whistle now in three or four years. Releasing them, stocking, and growing them and turning them lose, just doesn’t cut it. I love the wood duck. He’s the most beautiful of the waterfowl and we’ve got them all around. I’ve been putting wood duck boxes up for forty years or so. We did a count a couple years ago. I had ten wood duck boxes on ponds or wet places on the farm. When we checked them every one of them had a screech owl in it. The screech owls are fighting the wood ducks for their homes. I’d rather have wood ducks than screech owls but they’re a great little bird to watch and to listen to. And I’ve got plenty of eagles. We’ve got all the wildlife.

An image of woodcocks from Porter Hopkin's sketchbook.

What motivates you to conserve land?

“You can’t take it with you. And as far as I’m concerned, land is the most valuable, the most precious of all of the things that a person could own. I’ve owned land. I’ve felt that way ever since I was a little kid. It was natural to do it. I don’t think I did it on the farm in Baltimore County but I would have. I did not sell to anybody other than farmers.”

C. A. Porter Hopkins